(November 2025) Older adults have better cognitive function today than 20 years ago. It’s not yet clear why, but scientists generally think this might be due to the broad societal and individual lifestyle changes that we’ve seen in the world.

For decades, education has been championed as one such powerful defence against cognitive decline. Researchers have long noticed that people with more schooling tend to perform better on memory and thinking tests in later life.

Several theories have emerged why:

- Some scientists think learning may physically slow the actual loss of brain tissue over time (the “brain maintenance” hypothesis)

- Others argue that education helps the brain compensate for age-related damage, letting people maintain function even as parts of the brain decline (the “cognitive reserve” hypothesis).

- And some suggest that the link isn’t about ageing at all. Rather, that people who start out with stronger cognitive skills simply tend to get more education.

Testing these theories

To investigate this, an international team led by Professor Anders Fjell, who has conducted a huge amount of research in this area, analysed memory tests from more than 130,000 Europeans across 28 countries (forming the SHARE cohort) over multiple years, along with brain scans from thousands of these adults.

They also checked their results against those from the SHARE-HCAP (Harmonised Cognitive Assessment Protocol), a recent addition to the SHARE offer that was incorporated in Wave 9. This is a great sample because it can be compared with HCAP sister studies in the non-WEIRD countries China, India and South Africa (and one partially WEIRD country, Mexico).

Brain scan data came from 6,472 participants across seven countries, analysed as part of the Lifebrain consortium. By combining memory tests with brain scans, the team could see not just who remembered more, but how their brains changed over time.

This important work was able to overcome a major research challenge by providing large and heterogeneous samples with sufficient statistical power. The geographic coverage here – including Latin America, the US, and Europe – was highly valuable, because the relationship between education and dementia could easily vary across time and societies.

Revealing parallel lines

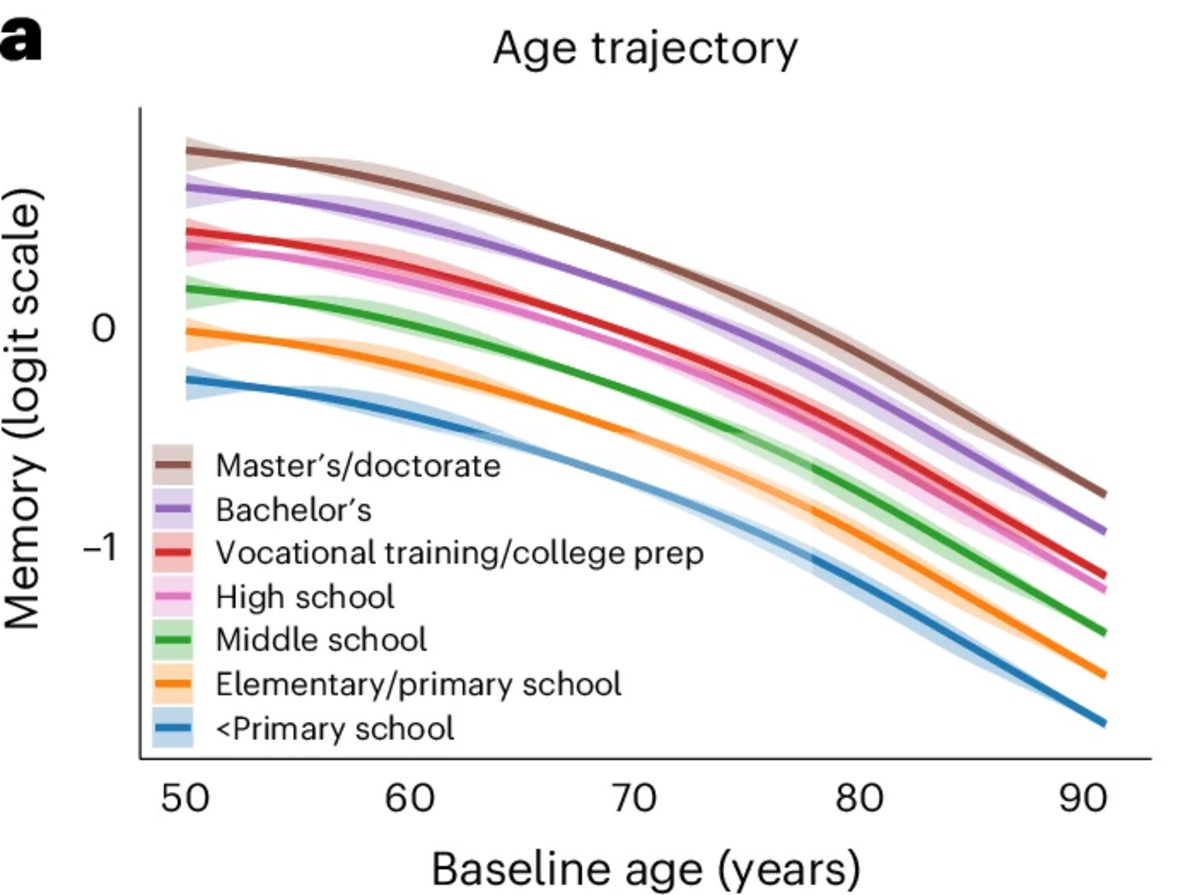

When the team tracked participants over time, they found that their memory scores declined at essentially the same rate regardless of education level. On graphs, the trajectories run in near-perfect parallel: people with master’s degrees or doctorates started higher and stayed higher, but their slopes downward matched those of people with minimal formal schooling.

Age and education effects on memory (adapted from Fjell et al., 2025).

The brain imaging data told a similar story. Among regions critical for memory (such as the hippocampus), structural changes progressed at comparable rates across education groups.

Combined these findings suggest that the difference is not in the journey (how fast the brain declines) but where people start from.

Starting points matter

This pattern points towards a less examined possibility: that the association between education and cognitive function largely reflects factors already in place during childhood.

In fact, when researchers factored in childhood indicators like self-reported math and language skills at age 10, or the number of books in the home during childhood, the education-memory link weakened substantially.

Perhaps most tellingly, people with higher education had larger intracranial volumes. This is a measure of maximum brain size that is established before adolescence and therefore unlikely to be influenced by later schooling.

Let’s go back to our two hypotheses.

Brain maintenance hypothesis: If education protects by preserving brain structure, highly educated individuals should show slower decline in memory-sensitive regions. They didn't.

Cognitive reserve hypothesis: If education builds resilience to brain changes, the correlation between brain decline and memory decline should be weaker in more educated groups. It wasn't.

Neither prediction held up.

What this means (and doesn’t mean)

The findings don’t diminish education’s value. The cognitive advantages associated with more schooling are real and substantial.

What the study challenges is the specific idea that education provides protection against the ageing process itself. This distinction matters for how we think about dementia prevention and brain health policies.

Thinking global

Recall that the researchers planned to compare their results to similar data from China, India, South Africa and Mexico.

Well, in doing so they found the patterns to be remarkably consistent despite vast differences in educational opportunities and mean scores.

This cross-cultural robustness suggests the findings reflect fundamental aspects of how cognition and education relate across human populations.

Moving forward

Rather than viewing education primarily as protection against future decline, we might understand it as contributing to a lifelong cognitive advantage established early and maintained through environmental factors that often correlate with educational attainment.

Education remains one of society’s most powerful levers for improving human flourishing. But we do need to be precise about what education does and doesn’t do for the ageing brain.

Study by Fjell, A.M., Rogeberg, O., Sørensen, Ø. et al. Reevaluating the role of education on cognitive decline and brain aging in longitudinal cohorts across 33 Western countries. Nat Med 31, 2967–2976 (2025).

URL: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03828-y

Picture: © Adobe Stock / Seventyfour